|

| http://googology.wikia.com/wiki/Googology |

He is usually credited as being the first googologist -- a person who studies large numbers. Large numbers like the googol -- equal to 10^(100) or 1 followed by 100 zeroes -- appear in parts of mathematics, but if big numbers crop up in psychiatric diagnoses then something has gone wrong, since for any practical purpose they may as well be considered infinite.

Here I'll show that the number of combinations of symptoms that can lead to a Personality Disorder (PD) diagnosis is about the same as the present estimate for the number of stars in the observable universe. Condensing this astronomical number into 10+1=11 possible labels is not only mind-bogging, but preposterous from a scientific point of view.

The previous post showed how 256 distinct groups of symptoms arise in the standard categorical definition of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). As a shorthand I refer to this as 256 phenotypes of BPD.

Combinations Leading to a Diagnosis of a Personality Disorder

The DSM 5 retained the 10 personality disorders (PDs) from the DSM IV. It also introduced an alternative hybrid model which I get to in the next post, but which unfortunately also suffers the same combinatorial catastrophe.Each disorder is defined by the appearance of at least X traits out of Y possible ones, where the list of traits, Y, is specific to each disorder. Going through this list gives a sum of 1408 different symptom combinations leading to a diagnosis of a single PD:

- Paranoid PD: at least 4 out of 7 symptoms = 64 paranoid phenotypes [1]

- Schizoid PD: at least 4 out of 7 symptoms = 64 schizoid phenotypes

- Schizotypal PD: at least 5 out of 9 = 256 schizotypal phenotypes

- Antisocial PD (AsPD): at least 3 out of 7 = 99 antisocial phenotypes

- Borderline PD: at least 5 out of 9 =256 borderline phenotypes

- Histrionic PD: at least 5 out of 8 = 93 histrionic phenotypes

- Narcissistic PD (NPD): at least 5 out of 9 = 256 narcissistic phenotypes

- Avoidant PD: at least 4 out of 7 = 64 avoidant phenotypes

- Dependent PD: at least 5 out of 8 = 93 dependent phenotypes

- Obsessive Compulsive PD: at least 4 out of 8 = 163 obsessive compulsive phenotypes

A symptom of one disorder may be similar to that of another; absence of remorse in AsPD resembles lack of empathy in NPD. Although they could occur together in any person, they are not the same trait and were, in fact, written in such a way as to be distinct in most cases.

Meeting the Criteria for More than One PD

"The typical patient meeting criteria for a specific personality disorder frequently also meets criteria for other personality disorders. Similarly, other specified or unspecified personality disorder is often the correct (but mostly uninformative) diagnosis, in the sense that patients do not tend to present with patterns of symptoms that correspond with one and only one personality disorder."

One arbitrary example, which points to the fundamental problem leading to large numbers and ambiguity of diagnoses, is that a person can meet the criteria for both NPD and BPD. That person could have any one of 256x256=65,623 combinations of PD symptoms. It only gets worse.

There are 10!/(8!)(2!)= 45 ways of meeting criteria for two diagnoses, 120 different ways for three, 210 ways for four, and so on up to 9 for nine and one for all 10. Indeed individuals have been diagnosed with more than 5 distinct PDs. But the principle is not the frequency that one finds distinct collections of symptoms, but the fact that such combinations are intrinsic to the definition of PDs, as a class of diseases in the DSM.

Taking the case that a person meets the criteria for all 10 PDs gives 64*64*256*99*256*93*256*64*93*163 = 6x10^(20) distinct groups of symptoms, or phenotypes that such a person could have. This number is 6 followed by 20 zeros. It is not as big as Archimedes number, but it is astronomically larger than common estimates for the number of species that have ever existed on earth, which is less than 10 billion -- or 1 followed by 10 zeros.

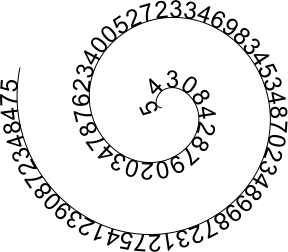

Combinatorial Explosion

Adding up all possibilities gives about 10^(21) distinct groups of symptoms that would meet the criteria of one or more PDs. Note that this doesn't even take into account the 'Not Otherwise Specified', or other unspecified or specified categories -- as if 10^(21) distinct groups of supposedly diagnostic symptoms were not enough!Number of Ways to be Diagnosed with BPD

In order to get a diagnosis of BPD, at least 5 of 9 criteria must be met leading to 256 unique combinations of symptoms. However such people may exhibit one or more symptoms of other personality disorders. Adding up items up on the symptom list for the remaining 9 PD's give 70 possible symptoms that a person with such a diagnosis may have. This means in fact that there are 256x[2^(70)] = 3x10^(23) ways to have Borderline based on the criteria of the DSM IV and 5 themselves. This is almost the same as Avogadro's number for the number of constituent atoms or molecules in a mole of a substance.If this isn't ridiculous, I don't know what is. Advanced statistics are used in most published papers in psychiatry, to test for significance, correlation or uncertainty, for example. A categorical system for diagnosing PDs has been around a long time, and with huge numbers like this staring one in the face, it's surprising not find published results about this combinatorial catastrophe in diagnosing PDs. It looks as if psychiatry does not take itself seriously.

One nice paper addressing this question focussed on bipolar disorders: Combinations of DSM-IV-TR Criteria Sets for Bipolar Disorders

Results: The number of possible combinations for the core episodes ranged from 163 for a manic episode to 37,001 for a mixed episode. When the full collection of specifiers that DSM-IV-TR applies to bipolar disorder was used, the number of combinations was over 5 billion. Conclusions: The precision of medical communication about bipolar disorder is called into question by the billions of different ways that the criteria for this diagnosis can be met. As DSM-V is developed, the possible combinations for each diagnostic criterion should be calculated, and the effect this number has on clinical communication should be considered.

At least 5 billion, or 5,000,000,000, for Bipolar Disorders is more than 10 orders of magnitude smaller [2] than 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 10^(23) possible ways to meet the diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder.

-----------------------------------------

[1] Choosing at least 4 out of 7 symptoms gives 7!/[(4!)(3!)] + 7!/[(5!)(2!)] + 7!/[(6!)(1!)] + 1 = 64 combinations that qualify for a diagnosis.

[2] An order of magnitude corresponds to one factor of ten: for instance 50 is one order of magnitude larger than 5, the number 500 is two orders of magnitude larger than 5, etc.

No comments:

Post a Comment